Bruno Frisoni on Roger Vivier

It always starts with a woman. This time her name is Petra, she’s 24 years old, lives in London, and is always stylishly dressed with a hint of retro. “She’s a Tilda Swinton playing to be Marlene Dietrich. There are always two women. One is wearing men’s shoes with a strass heel and satin, and the other is wearing small ankle boots with the Roger Vivier Ball heel in diamonds,” explains Bruno Frisoni, artistic director of extra-ordinaire shoemaker brand, Roger Vivier when outlining his creative process.

Petra is not in fact a real woman, but a figment of Frisoni’s imagination, who has fuelled his latest Rendez-vous Fall/Winter 2014 Collection, which was unveiled in Paris in January. “I always like to have a first drawing to create a universe, a back story. I need to start with a silhouette and then I start building things around her, adding shoes, jewels and other accessories. It’s like if you gave me a dollhouse and I start putting furniture in it; it creates a little story,” the designer explains, adding that a shoe never exists alone but is always part of a look.

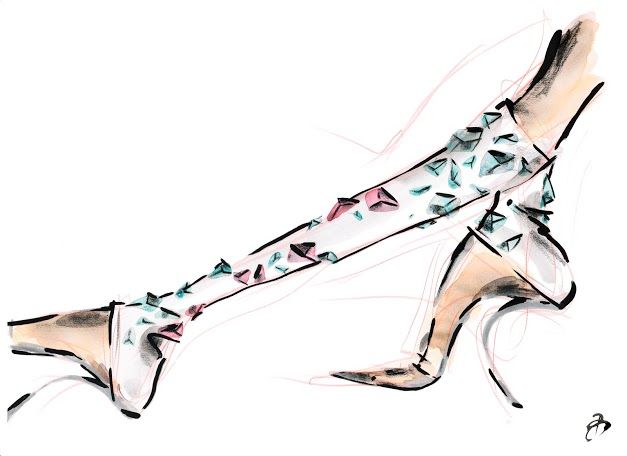

Frisoni has always loved to draw, and he does so quickly and energetically, always using a pink pen for his first draft – “I must have been born in pink, it really fits me” – and then using big Posca markers and color crayons. Frisoni’s drawings are more illustration than detailed constructions, “my drawings are precise, but vague at the same time. It comes out very quickly.

For me the energy that goes into the gesture is very important for the creation. I draw very fast and generally there is a lot of force to it. So much so that when I design a collection, I can get tennis elbow,” he explains.

VIVIER’S LEGACY

Before Christian Louboutin, Manolo Blahnik or Jimmy Choo, there was Roger Vivier. The legendary shoe designer started collaborating with Elsa Schiaparelli in the 1930s and went on to work with Christian Dior in the 1950s, creating a number of innovative heel shapes for the French couturier, including the inward curving “Choc” heel in 1959 and the stiletto heel (aiguille) in 1954. In 1963, he opened his own boutique in Paris and made the swooping comma heel, his signature. Another of his iconic creations was designed for Yves Saint Laurent in 1965, a square-toe shoe with a rectangular gold buckle, which, two years later, was popularized by Catherine Deneuve in the film “Belle de Jour.”

Vivier passed away at the age of 90 in 1998, but the brand was re-launched by Tod’s CEO Diego Della Valle in 2003 with Frisoni at its helm. At the time, the designer had already worked on accessories for Lanvin and Christian Lacroix, collaborated as a freelance designer at Trussardi, Givenchy, and Yves Saint Laurent in the late 1990s, before launching his eponymous line of luxury shoes in 1999, winning plaudits amongst celebrities for their display of feminine sophistication, coupled with a dash of humor.

At Roger Vivier, the 54-year-old designer has been able to indulge a certain level of design eccentricity, creating deliciously unusual shoes, building on Vivier’s legacy. Frisoni says he was first inspired by Vivier after visiting a retrospective of his work in 1987 at the Musée des Arts de la Mode in Paris. “I had kept the catalogue. So when I got a call to take on the designs at Vivier, all I had to do was look back into my memory,” he recalls, adding, “I remembered the lines, the craftsmanship, and the uniqueness of his designs. He was able to bring a high sophistication to his design while always keeping a certain freshness. He created beautiful, very sexy objects.”

“It was a sleeping beauty and the challenge was to bring it back to life and to make it an accessory house,” Frisoni says.

OLD AND NEW ICONS

Over the years, Frisoni has “re-interpreted” many of the codes first created by Roger Vivier, from the brand’s signature buckle to the sphere heels (a favorite of Marlene Dietrich), subtly updating the designs to meet the needs of today’s customers. “Back in the 50-70s, some of his sophisticated shoes would have been worn for a couple of hours only. Today, women expect to start and end the day with the same things, so you have to be practical,” he muses. So he has tinkered with the shock heel, “empting the arch a little bit,” because he found it was too heavy and he wanted to give it more height to “make the shoe look higher.”

Frisoni has also made a mark on the brand by developing new signature pieces, like the Prismick line with its distinctive multi-faceted angles first created in 2012. Prismick, he explains, emerged from his fascination with the use of 3D drawing in architecture and sculpture, where a curve is created by a succession of points joined together by lines. He cites the works of Xavier Veilhan and Antony Gormley, as well as Arik Levy as sources of inspiration. “I was looking at a collage that Vivier had done in the 90s, as he did quite a lot at that time, and suddenly it began to look quite obvious. I decided to look at the shock heel through a prism, and instead of designing a curve design, I designed with points and lines. Hence the name,” he says.

Inspiration comes in all forms, he points out – from a Herve Van der Straeten lamp on his desk that resembles a stiletto turned upside down, to a beautiful piece of coral. “Most of the time I start with images, photographs. I’m very spontaneous and it’s always a bit confused at the start. Then I start building a collection, layer by layer,” he says.

“But the starting point is often the heel.” he adds, “It is primarily what defines a silhouette. What you will remember is the heel!”

As first published in Blouin Lifestyle magazine