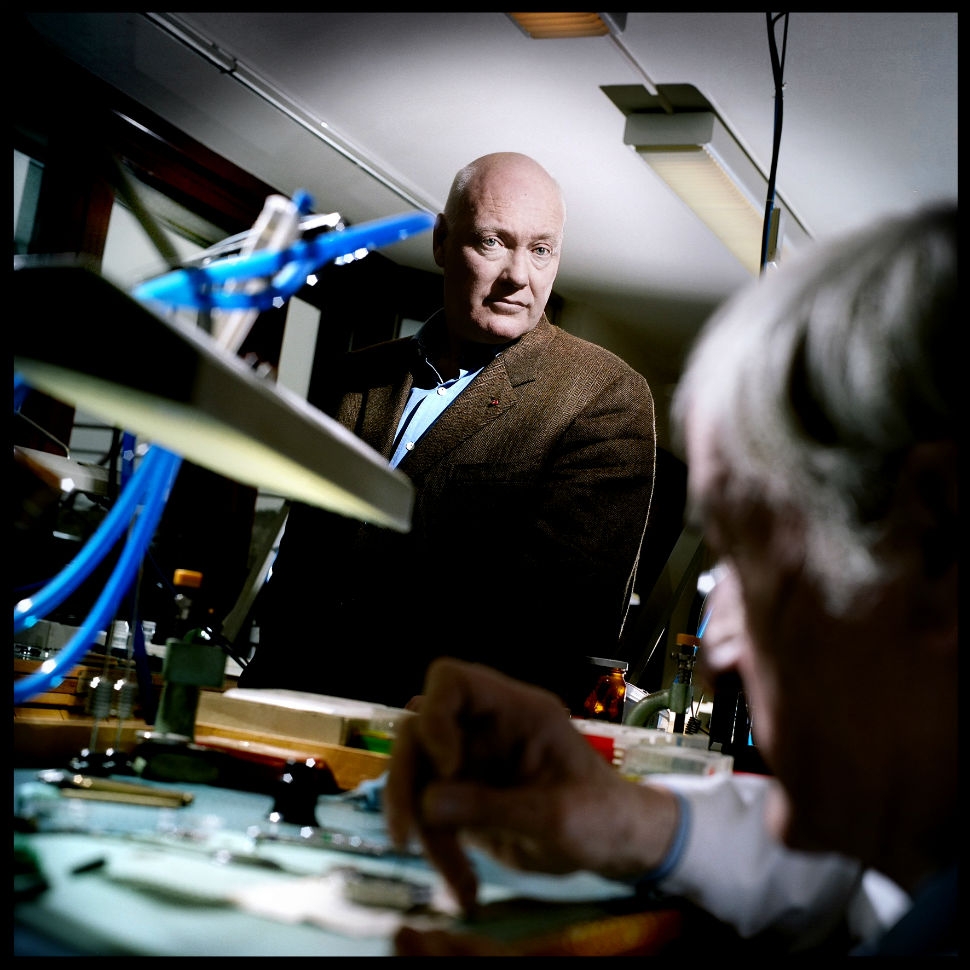

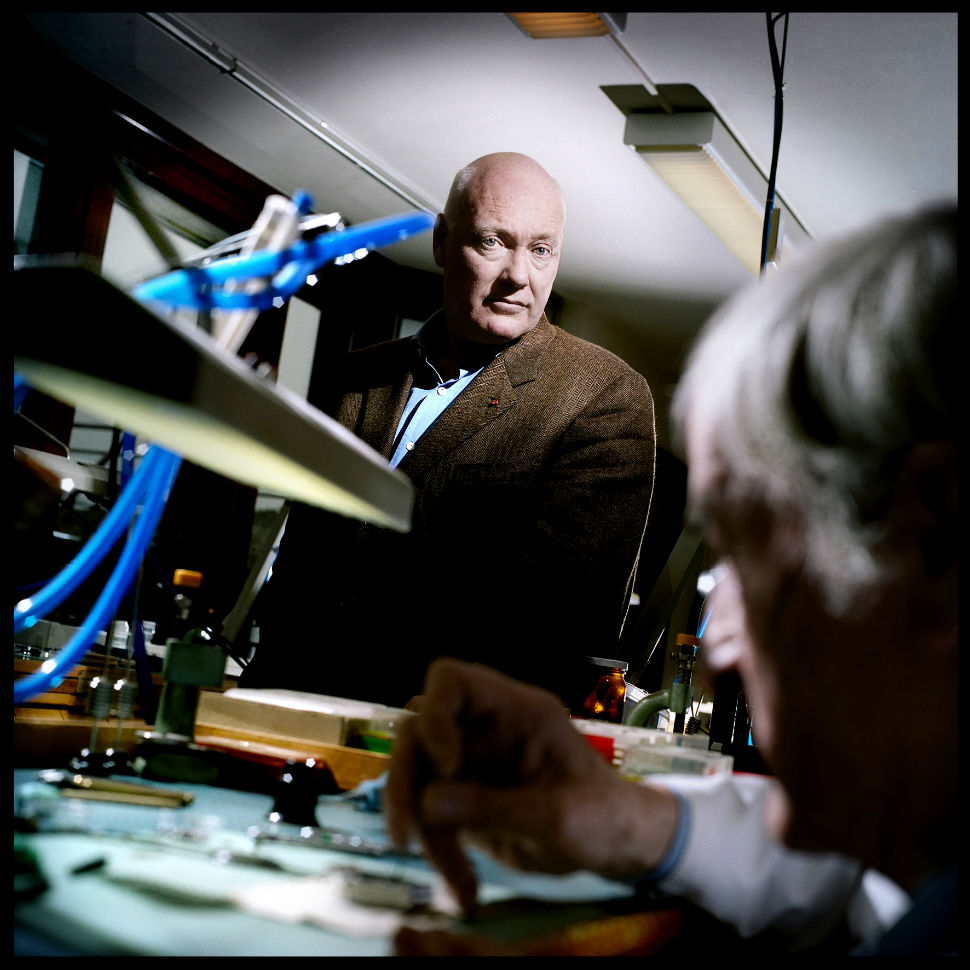

Meet Jean-Claude Biver, the Maverick Head of LVMH Watches

The revaluation of the Swiss franc in January created significant uncertainty for Swiss watchmakers that would destabilize some. Amidst general calls that the industry will need to raise prices, Jean-Claude Biver, the head of the watch division of the luxury group LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton, takes a contrarian view. “I’m going to try to go exactly the opposite of the industry, which I know is going to increase prices. I don’t want to do this for the moment,” he says in an interview, “First, how can we reduce our own operating costs, all the indirect costs, the licenses we pay, etc. Instead of looking at exterior factors, let’s look at internal factors (to make product pricing more competitive). Once I have done the work inside my own house, if we still need to increase prices, then okay. But we will not have a knee-jerk reaction and that may even allow us to gain market share.”

At 66, Biver is showing no signs of slowing down having recently taken over at the helm of Tag Heuer as interim CEO, while continuing to help guide Zenith and Hublot as head of the watch division of LVMH, which owns the three brands.

Over his near five-decade career in the watchmaking industry, Biver has transformed multiple brands, including Blancpain, Omega, and Hublot, and in the process earned a reputation as one of the visionaries and saviors of the Swiss watch industry. “He is a rare type of leader whose vision not only influenced his companies, but an entire industry,” says Harvard Business School professor Ryan Raffaelli, who devoted a case study last year to the businessman’s impact on the “Re-emergence of the Swiss Watch industry.”

“As one who studies innovation and leadership, it is unusual to come across a leader like Biver whose passion and love for their work has driven such high levels of creativity from their employees,” Raffaeli adds.

Having started in the industry as a young salesman for Audemars Piguet in the early 1970s and then joining Omega, Biver decided in 1982 to invest CHF24,000 with a friend to buy the Blancpain name, which had been dormant since 1961.

What happened next is the stuff of legend. While the Swiss watch industry was on the verge of collapse, fighting against inexpensive Japanese quartz watches, the businessman opted to re-launch Blancpain with classiclooking wristwatches that included traditional complications like moonphase, tourbillon, and minute repeater. A decade later he was selling the company for $70 million to the Swatch Group where a new adventure commenced: the revival of the ailing Omega brand.

With great marketing gusto — for example getting James Bond to wear an Omega watch — Biver led another turnaround in revenues.

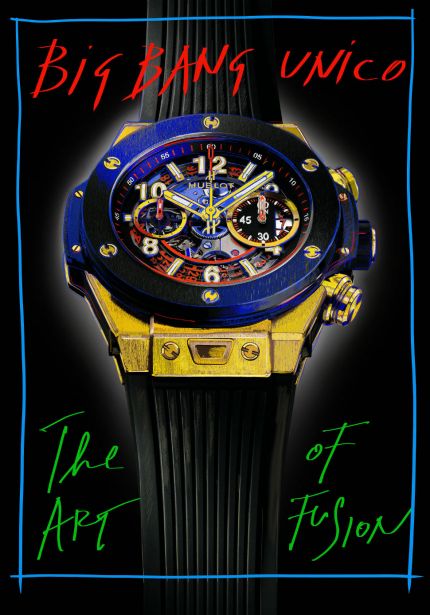

Then in 2004, he embarked on yet another adventure, setting out to revive Hublot. “In the 1980s, many of Biver’s peers believed the mechanical watch was a relic of the past and assumed quartz technology held the key to their future. Biver, however, was a maverick and contrarian. He was one of the first to redefine the mechanical watch as form of art and craftsmanship,” Rafaelli explains.

Biver’s latest challenge is the positioning of TAG Heuer. Since he took the reins of LVMH’s watch brands early last year, he has been hard at work reorganizing the TAG Heuer brand and scrapping satellite production like that of leather goods or other accessories.

“TAG Heuer is very strong in the price range of $1,000-3,500, — that’s its core business and I want the brand to focus on this core business. In the last years, TAG had done expensive high horology watches, but there is not enough room in that segment and I think TAG should concentrate in the segment where it is strong. TAG should be avant-garde, with materials, with new techniques, and even a connected watch,” says Biver, “we don’t need to be the 46th brand doing a tourbillon.”

Always with an eye to the future, Biver is convinced that TAG Heuer must now embrace the smart watch trend to appeal to a new generation of watch lovers, though he explains that he prefers to call it a “connected” watch because “connected means the watch connects you to all the information you need for transportation, your flights, your health, your blood pressure, so the word connected is more significant to what the watch does.”

“Young people don’t want to wear the same watch that older people are wearing. I think that for the lower-priced watches, smart watches will be a threat and you would be crazy to ignore them. It’s an opportunity for us and we must adapt to the tastes of a younger generation. TAG is in a price range where the connected watch starts to compete. They will never compete with a Hublot or a Zenith, but they will with the TAG’s entry price level and that’s why I’m concerned,” he explains.

Biver is determined that the TAG smart (connected) watch will be “different” to what is already out there. “I don’t think we should be a follower; as Confucius said, ‘only the dead fish swim with the current,’” he muses.

"I want the new watch to be TAG. So it will have a TAG look with TAG uniqueness and TAG features. It won’t be a phone, it won’t give you e-mails,” he says, noting that the first smart watch, the Swatch Access, was invented by Swatch in 1996.

And with much speculation surrounding the timing of the launch of this new connected watch, Biver quips he’s not in a hurry and just wants it right. Most likely, he says, the watch will not be released until the end of the year.

While his priority for now is TAG Heuer, Biver is not forgetting other brands under his LVMH division.

“Zenith is a hidden diamond and we have to shape it for the light to come out. It’s a phenomenal brand, but totally unexploited. It has to come back to life and we will start to work on this in the second half of the year,” he says.

“I like the challenge, to take on a brand, but for Zenith it will be the first time there is no need for restructuring; I just have to give it a new dynamism,” he adds.

Biver had previously said he plans to retire in 2020 to devote more time to his other passions, which include cheese-making and a business in restoring vintage cars. But now, having just been given the opportunity to lead three brands, Biver says he’ll probably go on for longer, though not at his current work rate of 18 hours a day, which he admits is “not sustainable long term.”

Whenever he decides to retire, Biver’s legacy will be broadly felt as today many of the most prestigious brands in the Swiss watch industry are led by former Biver protégées and so, “like his watches, the legacy Biver leaves behind will be timeless,” Raffaeli says.

As first published in Blouin Lifestyle Magazine